An efficient headless CMS on top of Wordpress - a.k.a the ACF Compiler!

Headless CMSs are becoming quite popular and make up one of the important ingredients of a JAMstack site. At SuprNation we have been tinkering with headless CMSs for quite a while and we have succesfully implemented one using Wordpress (WP), Advanced Custom Fields (ACF) and ACF-to-Rest API in one of our experiments. This trio can be used to implement a cheap and flexible headless CMS but as anyone who has worked with ACF knows, retrieving the underlying data can be slow if one relies on the current WP plugins. In this post I am going to describe how we have overcome this problem and introduce our open source initiative that drastically reduces the number of queries and round trips to the database.

Headless CMSs are becoming quite popular and make up one of the important ingredients of a JAMstack site. At SuprNation we have been tinkering with headless CMSs for quite a while and we have succesfully implemented one using Wordpress (WP), Advanced Custom Fields (ACF) and ACF-to-Rest API in one of our experiments. This trio can be used to implement a cheap and flexible headless CMS but as anyone who has worked with ACF knows, retrieving the underlying data can be slow if one relies on the current WP plugins. In this post I am going to describe how we have overcome this problem and introduce our open source initiative that drastically reduces the number of queries and round trips to the database.

Introduction

ACF together with WP custom types and ACF-to-Rest can provide the basis for a great headless CMS however due to the way ACF stores the data in the wp_postmeta and due to the API design of ACF (and ACF-to-Rest) this approach tends to be quite expensive.

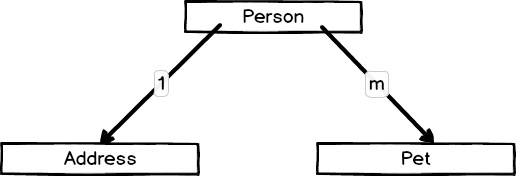

In order to understand the problem, let us create an object hierarchy using Person, Address and Pet types (![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() ). A Person will have a one-to-one relationship (Post-Object) with an Address and a one-to-many relationship (Relationship) with a Pet as illustrated below:

). A Person will have a one-to-one relationship (Post-Object) with an Address and a one-to-many relationship (Relationship) with a Pet as illustrated below:

In ACF we can add properties to types by associating a custom field group with each related custom type i.e. Person, Address and Pet. To create the Person, Address and Pet custom type one can use the custom-post-type-ui plugin or define these programatically. Let’s start by defining the Pet Field Group

| Field Name | Description |

|---|---|

pet_name |

The name of the pet. Type: Text. |

pet_age |

The age of the pet. Type: Number. |

and the Address Field Group

| Field Name | Description |

|---|---|

address_line_1 |

The address first line. Type Text. |

address_line_2 |

The address second line. Type Text. |

address_town |

The address town. Type Text. |

address_country |

The address country. Type Text. |

Finally, let’s define the Person Field Group

| Field Name | Description |

|---|---|

person_name |

The name of the person. Type: Text. |

person_surname |

The surname of the person Type: Text. |

person_address |

The address of the person. Type: Post Object of type address. |

person_pets |

The list of pets. Type: Relationship of type pet. |

Data Creation

Having modelled our types using custom post types and ACF fields, let us create a small data set of 5 posts: 3 Pets, 1 Address and 1 Person so that we can understand the inefficiencies.

Our 3 Pets will be

pet_name |

pet_age |

|---|---|

| Muccu | 4 |

| Puccu | 2 |

| Tuccu | 1 |

Our person, Mark, will live in a newly renovated area in Mars

field_name |

value |

|---|---|

| address_line_1 | 23, Mawrth Vallis Street |

| address_line_2 | N/A |

| address_town | Viking 1 |

| address_country | Mars |

and Mark will have Muccu, Puccu and Tuccu keeping him company

fieldname |

value |

|---|---|

person_name |

Mark |

person_surname |

Galea |

person_address |

Previous Address |

person_pets |

Muccu, Puccu and Tuccu |

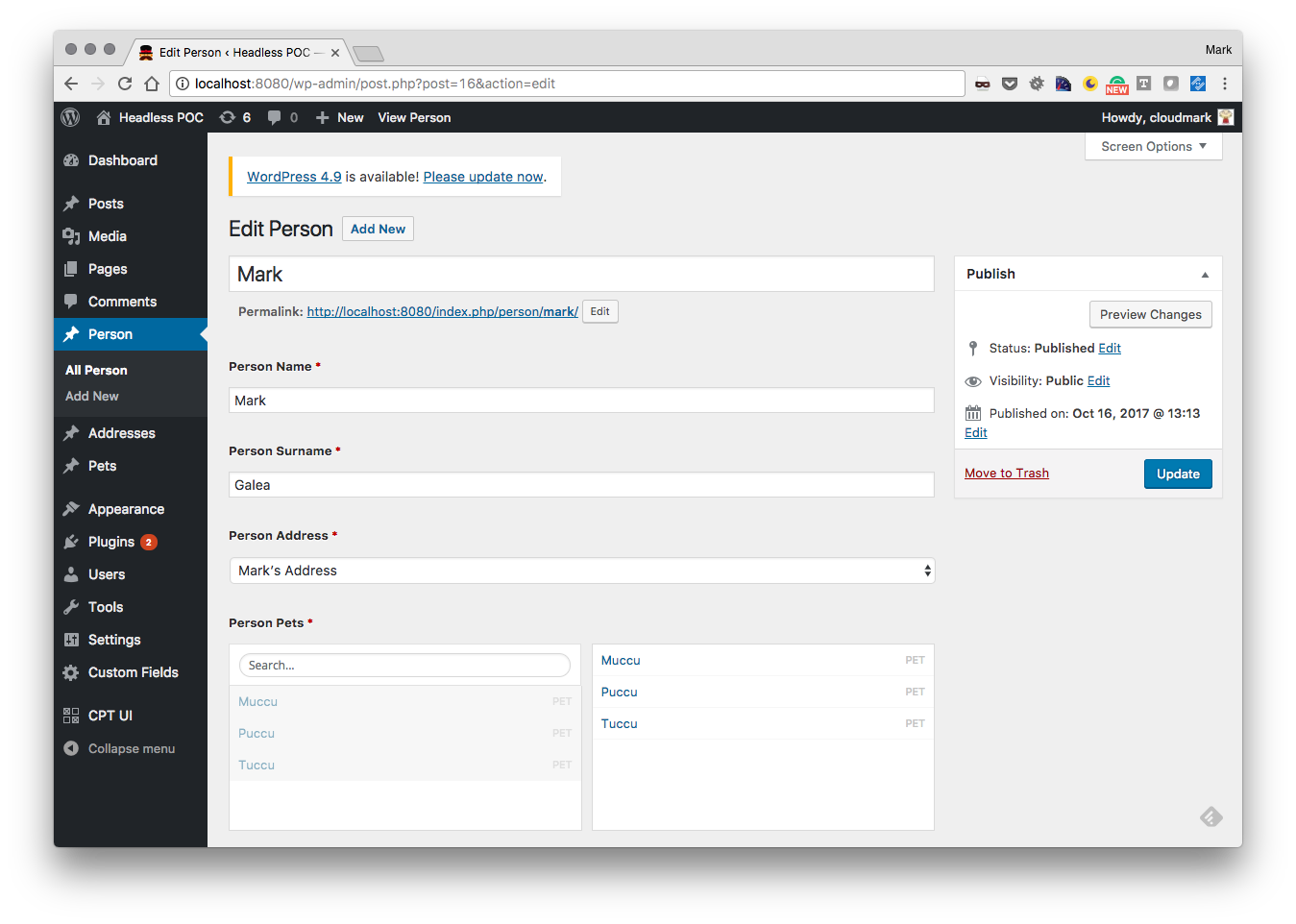

If you have created the data successfully the post Mark should look as follows:

Data Retrieval - The n+1 resource problem

Now that we have modelled our data and created our one person dataset (we went a bit overboard!), let’s install the acf-to-rest API to retrieve this (awesome, great, adorable.. ok I’ll stop!) person. Once the plugin is installed, we can retrieve all person data by accessing the endpoint http://<base-url>/wp-json/acf/v3/person.

[

{

"id": 16,

"acf": {

"person_name": "Mark",

"person_surname": "Galea",

"person_address": {

"ID": 15,

"post_author": "1",

"post_content": "",

"post_title": "Mark's Address",

"post_excerpt": ""

},

"person_pets": [

{

"ID": 11,

"post_author": "1",

"post_content": "",

"post_title": "Muccu"

},

{

"ID": 12,

"post_author": "1",

"post_content": "",

"post_title": "Puccu"

},

{

"ID": 13,

"post_author": "1",

"post_content": "",

"post_title": "Tuccu"

}

]

}

}

]

From the data we can observe that only the first level objects are resolved. To fully resolve the object graph, one would need to perform additional HTTP calls for each pet

- http://

/wp-json/acf/v3/pet/11 - http://

/wp-json/acf/v3/pet/12 - http://

/wp-json/acf/v3/pet/13

and address

- http://

/wp-json/acf/v3/address/15

Ok, you get the idea. This is quite inefficient! There must be another way!

Well it turns out that retrieving additional data by querying additional resource endpoints is not uncommon in the headless CMSs universe. In fact, most pricing models use this to their advantage. Apart from the price implications, such back and forth chatter imposes limits: limits on the number of data elements we can show to a user at once (no user will wait ad-infinitum) and limits in our modelling capabilities (we start flattening relationships to reduce API calls and costs).

Data Retrieval - A tale of multiple woes (Part 2)

In the previous section we have outlined the n+1 resource problem but there is more… not in a Steve Jobs way. Each relationship in our object graph comes with an expensive query cost which grows linearly with the number of results. In order to understand the costs let us analyse the query log associated with retrieving all posts of type Person. The query log which we will analyse is the following:

SELECT SQL_CALC_FOUND_ROWS wp_posts.ID FROM wp_posts WHERE 1=1 AND wp_posts.post_type = 'person' AND (wp_posts.post_status = 'publish') ORDER BY wp_posts.ID DESC LIMIT 0, 10

SELECT FOUND_ROWS()

SELECT wp_posts.* FROM wp_posts WHERE ID IN (16)

SELECT post_id, meta_key, meta_value FROM wp_postmeta WHERE post_id IN (16) ORDER BY meta_id ASC

SELECT meta_value FROM wp_postmeta WHERE post_id = 16 and meta_key LIKE '_%' AND meta_value LIKE 'field_%'

SELECT post_id, meta_value FROM wp_postmeta WHERE meta_key = 'field_59e4ace78916b'

SELECT * FROM wp_posts WHERE ID = 10 LIMIT 1

SELECT post_id, meta_value FROM wp_postmeta WHERE meta_key = 'field_59e4add78916c'

SELECT post_id, meta_value FROM wp_postmeta WHERE meta_key = 'field_59e4ade58916d'

SELECT * FROM wp_posts WHERE ID = 15 LIMIT 1

SELECT post_id, meta_value FROM wp_postmeta WHERE meta_key = 'field_59e4ae348916e'

SELECT wp_posts.* FROM wp_posts WHERE 1=1 AND wp_posts.ID IN (11,12,13) AND wp_posts.post_type IN ('post', 'page', 'attachment', 'custom_css', 'customize_changeset', 'person', 'address', 'pet') AND ((wp_posts.post_status <> 'trash' AND wp_posts.post_status <> 'auto-draft')) ORDER BY wp_posts.post_date DESC

SELECT t.*, tt.*, tr.object_id FROM wp_terms AS t INNER JOIN wp_term_taxonomy AS tt ON t.term_id = tt.term_id INNER JOIN wp_term_relationships AS tr ON tr.term_taxonomy_id = tt.term_taxonomy_id WHERE tt.taxonomy IN ('category', 'post_tag', 'post_format') AND tr.object_id IN (13, 12, 11) ORDER BY t.name ASC

SELECT post_id, meta_key, meta_value FROM wp_postmeta WHERE post_id IN (13,12,11) ORDER BY meta_id ASC

When a call is made to the ACF-to-Rest person endpoint (http://<base-url>/wp-json/acf/v3/person), a database query is performed to retrieve all post types of post_type=person from the wp_posts table.

SELECT SQL_CALC_FOUND_ROWS wp_posts.ID

FROM wp_posts

WHERE 1=1

AND wp_posts.post_type = 'person'

AND (wp_posts.post_status = 'publish')

ORDER BY wp_posts.ID DESC LIMIT 0, 10

SELECT wp_posts.*

FROM wp_posts

WHERE ID IN (16)

Once the list of post IDs are determined - in this case the Person with ID=16 - all ACF custom fields are retrieved by querying the wp_postmeta table. The query

SELECT post_id, meta_key, meta_value

FROM wp_postmeta

WHERE post_id IN (16)

ORDER BY meta_id ASC

will retrieve the following ACF field values and metadata links:

| PostId | Meta Key | Meta Value |

|---|---|---|

| 16 | _edit_last | 1 |

| 16 | _edit_lock | 1508161108:1 |

| 16 | person_name | Mark |

| 16 | _person_name | field_59e4ace78916b |

| 16 | person_surname | Galea |

| 16 | _person_surname | field_59e4add78916c |

| 16 | person_address | 15 |

| 16 | _person_address | field_59e4ade58916d |

| 16 | person_pets | a:3:{i:0;s:2:”11”;i:1;s:2:”12”;i:2;s:2:”13”;} |

| 16 | _person_pets | field_59e4ae348916e |

Analysing the retrieved rows we note that

- ACF Post Objects (one-to-one) store the referencing post ID in the

meta_value. E.g.person_addressrefers to the post with ID 15. - ACF Relationships (one-to-many) store a serialised array of post IDs. E.g.

person_petsare stored in the serialised arraya:3:{i:0;s:2:"11";i:1;s:2:"12";i:2;s:2:"13";}; the associated pets can be retrieved by retrieving posts with IDs11,12and13. - Normal fields encode their values as text and may require conversion. E.g. the value of

person_namedoes not need any conversions.

The semantics of what the values represent are based on our knowledge that person_address is a PostObject, person_pet is a Relationship and that person_name and person_surname are of type text (String). ACF-to-Rest needs to determine this information and thus needs to store this information in wp_postmeta table. ACF stores two key entries for each ACF field; <acf_field> and _<acf_field> (e.g. person_name and _person_name) in order to be able to retrieve the type metadata and value. The meta value stored under the meta key <acf_field> contains the encoded field value while the meta value stored under the meta key _<acf_field> contains a link to the value’s type metadata (or loosely a pointer to its type).

Retrieving type metadata is critical to interpret values correctly and ACF-to-Rest will perform a series of queries to obtain such type information. First ACF-to-Rest queries all field metadata to find all type metadata links

SELECT meta_value

FROM wp_postmeta

WHERE post_id = 16

AND meta_key LIKE '_%'

AND meta_value LIKE 'field_%'

then, using the result set

| Meta Value |

|---|

| field_59e4ace78916b |

| field_59e4add78916c |

| field_59e4ade58916d |

| field_59e4ae348916e |

ACF-to-Rest retrieves the type metadata by issuing a separate query for each meta_value

SELECT post_id, meta_value FROM wp_postmeta WHERE meta_key = 'field_59e4ace78916b'

SELECT post_id, meta_value FROM wp_postmeta WHERE meta_key = 'field_59e4add78916c'

SELECT post_id, meta_value FROM wp_postmeta WHERE meta_key = 'field_59e4ade58916d'

SELECT post_id, meta_value FROM wp_postmeta WHERE meta_key = 'field_59e4ae348916e'

In the query above, the meta_value corresponding to the meta_key = field_59e4ace78916b is

| Post Id | Meta Value |

|---|---|

| 10 | a:16:{s:4:”type”;s:4:”text”s:3:”key”;s:19:”field_59e4ace78916b”;…} |

From this meta_value ACF can determine that the type is text. Since person_name is related to _person_name which links to field_59e4ace78916b and since field_59e4ace78916b is of type text, ACF-to-Rest can determine that the value Mark is of type text and hence needs no further conversions.

Having retrieved the type metadata and the values, ACF-to-Rest will fire a set of queries to perform some sanity checks. First it will query all metadata links to make sure that they are of type acf. E.g. field_59e4ace78916b is linked to Post ID 10 so ACF-to-Rest will issue a query to retrieve Post ID 10 in order to make sure that the post_type is indeed acf.

SELECT * FROM wp_posts WHERE ID = 10 LIMIT 1

Secondly, ACF-to-Rest will partially load post relations to determine that they are published and that the data is from the said post_type. ACF-to-Rest checks the person_address by performing the query

SELECT * FROM wp_posts WHERE ID = 15 LIMIT 1

and the person_pets by firing multiple queries

SELECT wp_posts.* FROM wp_posts WHERE 1=1 AND wp_posts.ID IN (11,12,13) AND wp_posts.post_type IN ('post', 'page', 'attachment', 'custom_css', 'customize_changeset', 'person', 'address', 'pet') AND ((wp_posts.post_status <> 'trash' AND wp_posts.post_status <> 'auto-draft')) ORDER BY wp_posts.post_date DESC

SELECT t.*, tt.*, tr.object_id FROM wp_terms AS t INNER JOIN wp_term_taxonomy AS tt ON t.term_id = tt.term_id INNER JOIN wp_term_relationships AS tr ON tr.term_taxonomy_id = tt.term_taxonomy_id WHERE tt.taxonomy IN ('category', 'post_tag', 'post_format') AND tr.object_id IN (13, 12, 11) ORDER BY t.name

SELECT post_id, meta_key, meta_value FROM wp_postmeta WHERE post_id IN (13,12,11) ORDER BY meta_id

Heuristically if a post type has m instances, there would be around 9 + (5 * m) queries fired to retrieve and check the data. In our small hierarchy we would thus need

-

9 + (5 * 1)queries to retrieve the person, - another

(9 + (5 * 3))queries to fully resolve all pets and - another

(9 + (5 + 1))queries to fully resolve the address.

For a fully resolved object graph we would need around 14 + 24 + 14 = 52 queries. Ouch!

So doc, what’s the problem?

So what causes all these inefficiencies? From the analysis above we can summaries the inefficiencies as follows:

- There is an impedance mismatch between the object hierarchy created using WP custom yypes and ACF custom fields and the underlying database storage.

- ACF-to-Rest only resolves first level objects and full object graph resolution is expensive.

- Metadata required to determine what is represented by a value has to be loaded every time at runtime on retrieval and is expensive to retrieve.

The first problem is not WP specific. The object graph created using custom types and fields does not fit the relational model and there is naturally an impedance mismatch. All headless CMSs using a relational datamodel as their backing store will have such an impedance mismatch.

The second problem is basically a mismatch in requirements between the ACF API and ACF-to-Rest. Throughout the years the ACF API has been optimised to load single posts or a group of posts which have a certain type rather than objects or object graphs. Posts are the atoms that make up the WP universe and objects created by using custom types and fields have to be simulated on top of posts (saved in wp_post and wp_postmeta). ACF-to-Rest attempts to resolve objects and object graphs but fails since the underlying API is still stuck in its posts roots. The developers of ACF-to-Rest resolve the first level hierarchy but make no attempt to directly attack this problem.

Finally, the metadata problem. If we look at the query log we can determine that a good number of queries are performed to retrieve type metadata. Due to the fact that the end user is allowed to specify types and fields on these custom types dynamically, ACF is constrained to check the type metadata at runtime. In a way the ACF API trades safety for performance (which is good) because it cannot do any better. The biggest problem with this design is that normally one creates a type, associates some fields with that type and starts creating a number of posts. Very rarely does one change the initial type schema.

These three problems combined result in inefficient queries to the underlying database and hence slow retrieval of data.

Objects, Objects Everywhere - The ACF Compiler!

WP is a CMS rooted in the concept of posts but as the WP community matured, higher order concepts such as objects (or structures) were layered on top of the posts concept. ACF is one of the clear leaders in the abstraction race and through the use of custom post types and the Metadata API it has allowed users to shift from a posts world to an object oriented (or a structures) world. The shift in paradigm together with the introduction of the REST API in WP v4.7 has allowed WP to compete as a headless CMS with heavyweight contenders such as Contentful.

This is great news! A free headless CMS! Well… just because you can, does not mean you should, at least not with standard WP plugins. In the previous section we have summarised the problems with using WP as a headless CMS. If we had to reduce the last two points to their essence, we would end up with our opening statement “WP is a CMS rooted in the concept of posts” and this is the problem of using WP as a headless CMS. Every WP plugin which attempts to provide abstractions has to simulate this on top of the lower level post abstraction. Mapping between post world and object world is expensive and the object lie becomes less and less believable as the number of “objects” in the CMS increases.

Let’s look at the Person example again and work out an ACF equivalent in an OOP language.

@AllArgsConstructor

public class Person {

private String name;

private String surname;

private Address addressDto;

private List<Pet> pets;

}

@AllArgsConstructor

public class Address {

private String line1;

private String line2;

private String town;

private String country;

}

@AllArgsConstructor

public class Pet {

private String name;

private Integer age;

}

Immediately we realise that the Person representation in an OO language is more succinct. OO languages treat objects and relationships (between objects) as first class citizens and hence do not need to simulate objects on top of a post abstraction. Apart from being more readable, using a typed OO language allows us to annotate type information statically rather than dynamically making type information readily available. What if we could make use of the static type information present on the class and retrieve the posts directly from the WP database (without using any APIs)? Could this alleviate the problems identified in previous section? The answer is yes as is demonstrated through this open source initiative.

We start of by reading the class metadata and match this with the WP metadata by calling

val executionPlan = astCompiler.compile(classOf[Person])

Once verified, an execution plan is formulated which when executed will run the most optimal queries to retrieve the data . To retrieve all Person entries one just needs to call execute on the executionPlan

val persons = executionPlan.execute()

So what are the advantages of such an approach? First off, it does not use any of the inefficient WP APIs. The query log for the full graph resolution is the following:

-- Person

select cmspost0_.ID as ID1_1_, cmspost0_.post_author as post_aut2_1_, cmspost0_.post_content as post_con3_1_, cmspost0_.guid as guid4_1_, cmspost0_.post_modified as post_mod5_1_, cmspost0_.post_name as post_nam6_1_, cmspost0_.post_date as post_dat7_1_, cmspost0_.post_status as post_sta8_1_, cmspost0_.post_title as post_tit9_1_, cmspost0_.post_type as post_ty10_1_ from wp_posts cmspost0_ where cmspost0_.post_type='person' and (cmspost0_.post_status in ('publish' , 'inherit'))

select cmspostmet0_.meta_id as meta_id1_0_, cmspostmet0_.meta_key as meta_key2_0_, cmspostmet0_.meta_value as meta_val3_0_, cmspostmet0_.post_id as post_id4_0_ from wp_postmeta cmspostmet0_ where (cmspostmet0_.meta_key in ('id' , 'content' , 'person_pets' , 'person_address' , 'person_name' , 'person_surname')) and (cmspostmet0_.post_id in (16))

-- Pet

select cmspost0_.ID as ID1_1_, cmspost0_.post_author as post_aut2_1_, cmspost0_.post_content as post_con3_1_, cmspost0_.guid as guid4_1_, cmspost0_.post_modified as post_mod5_1_, cmspost0_.post_name as post_nam6_1_, cmspost0_.post_date as post_dat7_1_, cmspost0_.post_status as post_sta8_1_, cmspost0_.post_title as post_tit9_1_, cmspost0_.post_type as post_ty10_1_ from wp_posts cmspost0_ where cmspost0_.post_type='pet' and (cmspost0_.ID in (11 , 12 , 13)) and (cmspost0_.post_status in ('publish'))

select cmspostmet0_.meta_id as meta_id1_0_, cmspostmet0_.meta_key as meta_key2_0_, cmspostmet0_.meta_value as meta_val3_0_, cmspostmet0_.post_id as post_id4_0_ from wp_postmeta cmspostmet0_ where (cmspostmet0_.meta_key in ('pet_name' , 'pet_age' , 'id')) and (cmspostmet0_.post_id in (11 , 12 , 13))

-- Address

select cmspost0_.ID as ID1_1_, cmspost0_.post_author as post_aut2_1_, cmspost0_.post_content as post_con3_1_, cmspost0_.guid as guid4_1_, cmspost0_.post_modified as post_mod5_1_, cmspost0_.post_name as post_nam6_1_, cmspost0_.post_date as post_dat7_1_, cmspost0_.post_status as post_sta8_1_, cmspost0_.post_title as post_tit9_1_, cmspost0_.post_type as post_ty10_1_ from wp_posts cmspost0_ where cmspost0_.post_type='address' and (cmspost0_.ID in (15)) and (cmspost0_.post_status in ('publish'))

select cmspostmet0_.meta_id as meta_id1_0_, cmspostmet0_.meta_key as meta_key2_0_, cmspostmet0_.meta_value as meta_val3_0_, cmspostmet0_.post_id as post_id4_0_ from wp_postmeta cmspostmet0_ where (cmspostmet0_.meta_key in ('address_town' , 'id' , 'address_country' , 'address_line_2' , 'address_line_1')) and (cmspostmet0_.post_id in (15))

From the query log we can observe that for a complete object graph resolution we only need 6 queries as opposed to the 52 queries required when using the WP plugins. The second advantage is that our system is aware of relationships between objects. To understand this let us remove the Address relationship from the Person class as follows

public class Person {

private String name;

private String surname;

private List<Pet> pets;

}

public class Pet {

private String name;

private Integer age;

}

Our system is able to identify that the relationship is no longer present and optimise the queries generated as follows:

-- Person

select cmspost0_.ID as ID1_1_, cmspost0_.post_author as post_aut2_1_, cmspost0_.post_content as post_con3_1_, cmspost0_.guid as guid4_1_, cmspost0_.post_modified as post_mod5_1_, cmspost0_.post_name as post_nam6_1_, cmspost0_.post_date as post_dat7_1_, cmspost0_.post_status as post_sta8_1_, cmspost0_.post_title as post_tit9_1_, cmspost0_.post_type as post_ty10_1_ from wp_posts cmspost0_ where cmspost0_.post_type='person' and (cmspost0_.post_status in ('publish' , 'inherit'))

select cmspostmet0_.meta_id as meta_id1_0_, cmspostmet0_.meta_key as meta_key2_0_, cmspostmet0_.meta_value as meta_val3_0_, cmspostmet0_.post_id as post_id4_0_ from wp_postmeta cmspostmet0_ where (cmspostmet0_.meta_key in ('id' , 'content' , 'person_pets' , 'person_address' , 'person_name' , 'person_surname')) and (cmspostmet0_.post_id in (16))

-- Pet

select cmspost0_.ID as ID1_1_, cmspost0_.post_author as post_aut2_1_, cmspost0_.post_content as post_con3_1_, cmspost0_.guid as guid4_1_, cmspost0_.post_modified as post_mod5_1_, cmspost0_.post_name as post_nam6_1_, cmspost0_.post_date as post_dat7_1_, cmspost0_.post_status as post_sta8_1_, cmspost0_.post_title as post_tit9_1_, cmspost0_.post_type as post_ty10_1_ from wp_posts cmspost0_ where cmspost0_.post_type='pet' and (cmspost0_.ID in (11 , 12 , 13)) and (cmspost0_.post_status in ('publish'))

select cmspostmet0_.meta_id as meta_id1_0_, cmspostmet0_.meta_key as meta_key2_0_, cmspostmet0_.meta_value as meta_val3_0_, cmspostmet0_.post_id as post_id4_0_ from wp_postmeta cmspostmet0_ where (cmspostmet0_.meta_key in ('pet_name' , 'pet_age' , 'id')) and (cmspostmet0_.post_id in (11 , 12 , 13))

Class Annotations

Our previous example is a bit simplified. In reality we would need to annotate the classes so that the ACF Compiler can work out the most optimal queries and verify that the metadata in WP matches the static metadata on the class. Fortunately, the annotations are pretty self explanatory. The complete Person example is as follows:

@Getter

@PostType("person")

public class Person {

@Alias("person_name")

private String name;

@Alias("person_surname")

private String surname;

@Alias("person_address")

private Address addresses;

@Alias("person_pets")

private List<Pet> pets;

}

@Getter

@PostType("address")

public class Address {

@Alias("address_line_1")

private String line1;

@Alias("address_line_2")

private String line2;

@Alias("address_town")

private String town;

@Alias("address_country")

private String country;

}

@Getter

@PostType("pet")

public class Pet {

@Alias("pet_name")

private String name;

@Alias("pet_age")

private Integer age;

}

val executionPlan = astCompiler.compile(classOf[Person])

val persons = executionPlan.execute()

Graph Cycles and Caching

Objects in an object graph may be referenced from multiple objects and may contain cycles. Cycles and multiple references lead to inefficient queries and hence we need a way to identify whether two objects are equal. In WP equality can be based on the post identifier (finally some good came out of posts!). In the ACF Compiler we will detect whether a class implements the CmsPostIdentifier interface and if it does, the compiler will reuse objects which have already been loaded through multiple references or cycles. The Person example above can be update as follows:

@Getter

@PostType("person")

public class Person implements CmsPostIdentifier {

@Alias("id")

private Long wordpressId;

@Alias("person_name")

private String name;

@Alias("person_surname")

private String surname;

@Alias("person_address")

private Address addresses;

@Alias("person_pets")

private List<Pet> pets;

}

@Getter

@PostType("address")

public class Address implements CmsPostIdentifier {

@Alias("id")

private Long wordpressId;

@Alias("address_line_1")

private String line1;

@Alias("address_line_2")

private String line2;

@Alias("address_town")

private String town;

@Alias("address_country")

private String country;

}

@Getter

@PostType("pet")

public class Pet implements CmsPostIdentifier {

@Alias("id")

private Long wordpressId;

@Alias("pet_name")

private String name;

@Alias("pet_age")

private Integer age;

}

Note that we added a field wordpressId in the above example which stores the WP identifier and hence hold the definition of equality. The compiler will take care of setting the correct value to this field.

Conclusion

Historically WP was a CMS rooted in the concept of a “post” however as of version 3.0, WP enabled users to add custom post types and also opened the Metadata API. Custom Post Types and ACF (which builds on top of the Metadata API) have allowed WP to move up the abstraction hierarchy and allow users to think in terms of objects rather than posts. Mapping between post world and object world is expensive in WP and might be a limiting factor in real world applications.

In this blog post I have outlined our efforts to directly address this issue and reduce retrieval time drastically. On our production environments we have seen bootstrap times drop from 1 minute to a couple of seconds. We have tested this system extensively and we would love to share our initiative with the community.

In the coming days we will create a generic test suite (our tests are too domain specific) to make sure things do not regress. We will also explain in more depth how one can use this library as well as give some design outline so that you guys can understand how everything fits together. We are also experimenting with execution of queries in parallel (some queries are independent) but it’s still early days.

If you have been working with WP and you are using a similar approach, please reach out - we would love to collaborate. I feel super excited to be in a position where we can give something back! We owe it to the community. If you want to contribute have a look at the project page Github - we will be updating it in the coming days. If you have questions, comments (or insults) please comment below. Stay safe, stay tuned and keep hacking!