Crawling the Web using Actors

Here is a simple fact: the free lunch is over. CPUs aren’t getting any faster but rather they are getting wider. Nowadays we can find multiple execution cores within one chip with shared memory or virtual cores sharing a single physical execution core however CPU’s aren’t doubling in speed. What this means is that concurrency is inevitable and we have to adapt to this new programming landscape in order to create event-driven, scalable, resilient and (hence) responsive programs. In this blog we are going to introduce the Actor Model and create a Crawl Server using Akka and Scala to piece everything together.

Here is a simple fact: the free lunch is over. CPUs aren’t getting any faster but rather they are getting wider. Nowadays we can find multiple execution cores within one chip with shared memory or virtual cores sharing a single physical execution core however CPU’s aren’t doubling in speed. What this means is that concurrency is inevitable and we have to adapt to this new programming landscape in order to create event-driven, scalable, resilient and (hence) responsive programs. In this blog we are going to introduce the Actor Model and create a Crawl Server using Akka and Scala to piece everything together.

Actor Model

We humans are constantly bombarded with stuff we need to get done; you need to take your car in for service and you just realised that you forgot to buy your wife’s anniversary gift! Ouch! How can we deal with all this concurrency? The answer is simple - we take one task at a time, do it well and move on to the next task. If the task at hand takes a very long time then we will be stuck doing that task for a very long time before we can pick something else. If we want more stuff to happen at once we will need to delegate; I can buy that gift for you if you want!

An actor in an Actor Model follows exactly the same strategy. We can submit tasks to an actor by sending messages to its private mailbox. Each actor will pick messages in order, execute the first one and move on. While an actor is executing a task (message) it is in its own fortress; no other thread can execute within the same actor instance and the actor is not aware of any other messages in its mailbox. With the guarantee that one and only one message can execute at any point in time we do not need to guard against critical sections using locks, semaphores or other low-level constructs. Since an actor can do one task at a time how do we create programs which do a lot of things simultaneously? Similar to humans we can achieve concurrency by instantiating more than one actor.

Now that I have your attention let us start off with a simple Hello World example.

Hello World!

Creating an actor is extremely simple. First thing we need to do is import the akka library.

name := "crawler"

version := "1.0"

scalaVersion := "2.11.8"

libraryDependencies += "com.typesafe.akka" % "akka-actor_2.11" % "2.4-SNAPSHOT"

resolvers += "Akka Snapshot Repository" at "http://repo.akka.io/snapshots/"

Next we will extend our HelloWorld class from Actor and implement the receive partial function.

class HelloWorld extends Actor {

override def receive = {

case "Hello" => println("World!")

}

}

That’s it, we are done! Let’s create the necessary scaffold to run this actor.

object HelloWorldMain extends App {

val system:ActorSystem = ActorSystem("HelloWorldSystem")

val helloWorld:ActorRef = system.actorOf(Props[HelloWorld], "HelloWorld")

helloWorld ! "Hello"

}

We first create an ActorSystem - you can think of an ActorSystem as a community were all actors live and interact. Besides creating a sandbox, an ActorSystem will also give us access to the root actor which will give life to all other actors. Using the root actor we create a HelloWorld actor using system.actorOf and send a “Hello” message to the this actor using the tell operator (!). The HelloWorld actor will receive the “Hello” message and print “World!” to system out.

The discussed HelloWorld example is atypical for two reasons i) messages are represented as raw strings and ii) the HelloWorld actor never replies (println does not count as a reply because no messages are being sent). We can improve this by creating a HelloWorld companion object with two case classes: Hello and World and update our listing as follows:

object HelloWorld {

case class Hello()

case class World()

}

class HelloWorld extends Actor {

override def receive = {

case Hello => sender ! World()

}

}

What is important to note is that messages make an actor system tick. An actor which does not send any messages (stateless) is a useless actor. Akka will try to protect us from directly trying to reference the actor’s internals by giving us an ActorRef instead of the “real” instance. Akka will also prevent us from instantiating actors using the new keyword (e.g. new HelloWorld()).

Supervisor Hierarchies

In the previous section we have glossed over the fact that actors are able to create other actors; we obtain access to the root actor by creating an Actor System. Each actor has the ability to create other actors and these actors can create other actors and so on (it’s turtles all the way down!).

These actors form a tree hierarchy due to the fact that each actor has one and only one parent. As their human counterparts, actors die. When an actor dies their parent gets notified and will decide on how to proceed (e.g. restart the child actor, ignore the child actor’s death, escalate the death and so on). This supervision hierarchy marks one of the corner stones for Actor Systems design; embracing failure is an essential trait to survive in this concurrent distributed jungle. In the actor domain we refer to this as the “Let it crash” philosophy.

Actor System - Crawl the Web

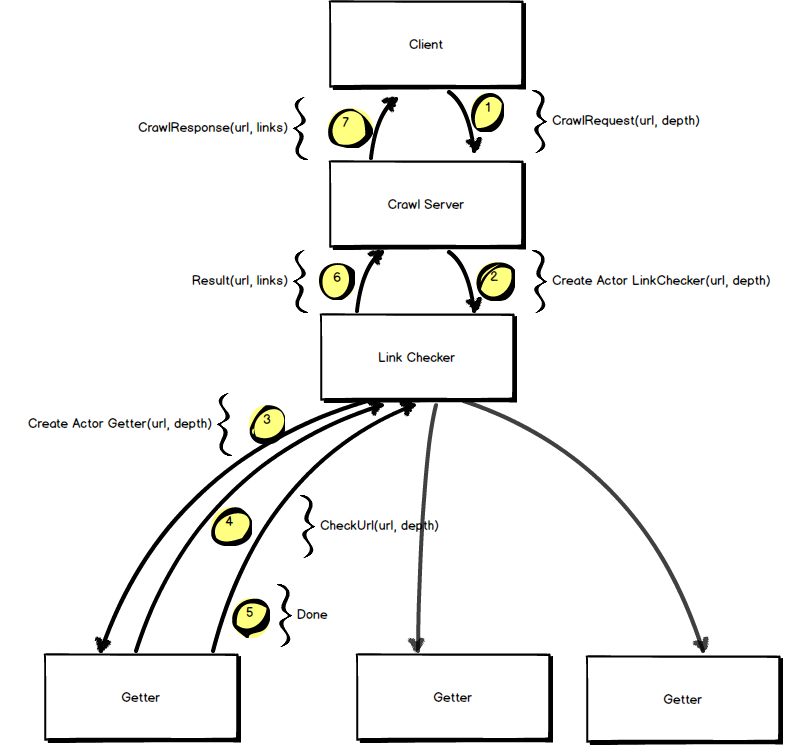

Having covered what actors are and some of their basic capabilities, let us design a web crawler system. My suggestion when designing actor systems is to i) treat the actors as living entities and divide the task as if you were dividing it amongst real people ii) imagine the dialogue between these people and create messages to represent such a conversation iii) summarise all actors and messages including all communication lines in a diagram. To create a Crawl Server we will need the following actors and message flows:

- [1] A

Clientactor will send aCrawlRequestto theCrawlServer. - [2] The

CrawlServerwill delegate the request to a newLinkCheckeractor unless a url request to the same domain is already ongoing. In such a case the client will be added to the list of recipients for the current ongoing message and will receive a reply once the original url request is fulfilled. - [3] The

LinkCheckeractor will track all URLs being crawled and will delegate the fetching of URLs by instantiating individualGetteractors. TheLinkCheckeris what handles the original request and what coordinates the link retrieval process. - [4] The

Getteractor will retrieve the page content, collect all anchor tags and send a message back to theLinkChecker. TheGetteris only concerned with the current url and is not aware of other URLs that need to be downloaded in order to fulfill the request. - [5] Once all links are retrieved, the

Getterwill send aDonemessage and die. - [6] When the

LinkCheckerreceives aDonemessage it will collate all links found and send aResultmessage to theCrawlServerand die. - [7] When the

CrawlServerreceives aResultmessage it will reply to the client(s) by sending aCrawlResponse.

Now that we have the blue print set up, let us implement each actor.

Getter

The Getter is the workhorse of our system it is the actor which will fetch the bits and bytes of a web page and parse the HTML page for links. In order to facilitate retrieval and parsing of URLs we will make use of async-http-client and jsoup respectively. To download these libraries simply update the build.sbt as follows:

name := "crawler"

version := "1.0"

scalaVersion := "2.11.8"

libraryDependencies += "com.typesafe.akka" % "akka-actor_2.11" % "2.4-SNAPSHOT"

libraryDependencies += "com.ning" % "async-http-client" % "1.9.40"

libraryDependencies += "org.jsoup" % "jsoup" % "1.8.3"

resolvers += "Akka Snapshot Repository" at "http://repo.akka.io/snapshots/"

resolvers += "Java.net Maven2 Repository" at "http://download.java.net/maven/2/"

Next, let us create a WebClient helper which will package neatly the HTTP request in a promise.

object WebClient {

val config = new AsyncHttpClientConfig.Builder()

val client = new AsyncHttpClient(config

.setFollowRedirect(true)

.setExecutorService(Executors.newWorkStealingPool(64))

.build())

def get(url: String): Future[String] = {

val promise = Promise[String]()

val request = client.prepareGet(url).build()

client.executeRequest(request, new AsyncCompletionHandler[Response]() {

override def onCompleted(response: Response): Response = {

promise.success(response.getResponseBody)

response

}

override def onThrowable(t: Throwable): Unit = {

promise.failure(t)

}

})

promise.future

}

}

Note that we could retrieve the HTTP request synchronously however remember that whilst an actor is busy doing something, the actor is in its own fortress. If the HTTP request takes 30 seconds to finish, the Getter actor will spend 30 second spin waiting. In order to make the best use of our resources we will use the async http client thread pool and only send a message to the actor with the content once that content is retrieved.

Now that we have all the ingredients let us cook up (a delicious) Getter actor.

object Getter {

case class Done() {}

}

class Getter(url: String, depth: Int) extends Actor {

import Getter._

implicit val ec = context.dispatcher

val currentHost = new URL(url).getHost

WebClient.get(url) onComplete {

case Success(body) => self ! body

case Failure(err) => self ! Status.Failure(err)

}

def getAllLinks(content: String): Iterator[String] = {

Jsoup.parse(content, this.url).select("a[href]").iterator().asScala.map(_.absUrl("href"))

}

def receive = {

case body: String =>

getAllLinks(body)

.filter(link => link != null && link.length > 0)

.filter(link => !link.contains("mailto"))

.filter(link => currentHost == new URL(link).getHost)

.foreach(context.parent ! LinkChecker.CheckUrl(_, depth))

stop

case _: Status.Failure => stop()

}

def stop(): Unit = {

context.parent ! Done

context.stop(self)

}

}

As soon as the actor is initialised the actor will initiate a call to retrieve the contents of the URL - WebClient.get(url). If the call completes successfully the HTML body is sent to the actor otherwise a Failure message is sent. Even though we could have called directly the receive partial function we always communicate with the actor using messages - messages are kings! Calling the receive partial function directly would break the guarantees provided by the Actor System. Always, always, always (did I say always?) communicate with Actors through messages.

When the actor receives the content body, all links are retrieved by calling the getAllLinks function and an individual CheckUrl message is sent to the LinkChecker actor - context.parent ! LinkChecker.CheckUrl(_, depth). Once all links are communicated back to the LinkChecker, the Getter will send a Done message to the LinkChecker and die (stop function). Note that the getAllLinks filters out invalid links, mailto links, and also links which are not within the root domain.

If the Getter receives a Failure message the Getter will send a Done message and die.

Link Checker

Web pages are filled with links and these links can create cycles. In order to prevent our crawler from crawling the web ad infinitum we will track all links and make sure that they are unique. The LinkChecker is implemented as follows:

object LinkChecker {

case class CheckUrl(url: String, depth: Int){}

case class Result(url: String, links: Set[String]) {}

}

class LinkChecker(root: String, originalDepth: Integer) extends Actor {

var cache = Set.empty[String]

var children = Set.empty[ActorRef]

self ! CheckUrl(root, originalDepth)

def receive = {

case CheckUrl(url, depth) =>

if (!cache(url) && depth > 0)

children += context.actorOf(Props[Getter](new Getter(url, depth-1)))

cache += url

case Done =>

children -= sender

if (children.isEmpty) context.parent ! Result(root, cache)

}

}

When a LinkChecker is initialised it will send a message to itself to check the root URL. When a CheckUrl message is received from the initialisation process or from the Getter actor, the URL is checked to determine whether it was visited before by looking up its corresponding entry in the actor’s local cache - !cache(url). The URL is also checked to make sure that the link depth has not been exceeded. If these two conditions are satisfied a Getter actor is initialised (with one less depth) and the URL is added to the local cache. When the Done message is received the LinkChecker actor will check whether there are any ongoing requests and if all requests have terminated the parent (CrawlServer) is notified with the result - Result(root, cache).

Crawl Server

The CrawlServer actor is responsible for delegating requests to the LinkChecker actor, wait for a reply and send the reply back to the Client(s). Think about this actor as the receptionist of your office building. When a request comes through the CrawlServer will initiate a LinkChecker actor. In order to prevent Client’s from requesting the same URL whilst another request to the same URL is ongoing, the server will cluster incoming requests to the same URL together (ignoring depth).

object CrawlServer {

case class CrawlRequest(url: String, depth: Integer) {}

case class CrawlResponse(url: String, links: Set[String]) {}

}

class CrawlServer extends Actor {

val clients: mutable.Map[String, Set[ActorRef]] = collection.mutable.Map[String, Set[ActorRef]]()

val controllers: mutable.Map[String, ActorRef] = mutable.Map[String, ActorRef]()

def receive = {

case CrawlRequest(url, depth) =>

val controller = controllers get url

if (controller.isEmpty) {

controllers += (url -> context.actorOf(Props[LinkChecker](new LinkChecker(url, depth))))

clients += (url -> Set.empty[ActorRef])

}

clients(url) += sender

case Result(url, links) =>

context.stop(controllers(url))

clients(url) foreach (_ ! CrawlResponse(url, links))

clients -= url

controllers -= url

}

}

Note that we are using mutable maps - imagine having to deal with maps concurrently using our good old locks and semaphores!!

Dealing with Timeouts

When dealing with web page retrieval we need to take special care in ensuring that the remote party is still responsive. In order to implement this requirement we will set a receive timeout on the LinkChecker which will trigger a ReceiveTimeout message after 10 seconds - context.setReceiveTimeout(10 seconds). The timer will automatically restart as soon as a new message is received; be it a new link - CheckUrl or a fulfilled message - Done. Once the timer has triggered we are guaranteed that the actor has not received any messages within the stipulated time (10 seconds) and given our semantics we will terminate all ongoing requests by killing all Getter actors.

class LinkChecker(root: String, originalDepth: Integer) extends Actor {

...

self ! CheckUrl(root, originalDepth)

context.setReceiveTimeout(10 seconds)

def receive = {

case CheckUrl(url, depth) => ...

case Done => ...

case ReceiveTimeout => children foreach (_ ! Getter.Abort)

}

}

In order to terminate the child actors we can opt to use the context.stop(childActor) which terminates the child actor immediately. To play nicely, we will instead send an Abort message to the child actors so as to allow the individual actors to cleanup resources and die.

class Getter(url: String, depth: Int) extends Actor {

...

def receive = {

case body: String => ...

case _: Status.Failure => ...

case Abort => stop()

}

...

}

Putting it all together

As an example let us create a CrawlServer and submit a request to crawl https://www.bbc.co.uk/ up to 2 levels of depth. To facilitate the communication with the CrawlServer we will create a surrogate Main actor which will wait for the CrawlServer reply - CrawlResponse(root, links).

object Main extends App {

println(s"Current Time ${System.currentTimeMillis}")

val system = ActorSystem("Crawler")

val receptionist = system.actorOf(Props[CrawlServer], "CrawlServer")

val main = system.actorOf(Props[Main](

new Main(receptionist, "https://www.bbc.co.uk/", 2)), "BBCActor")

}

class Main(receptionist: ActorRef, url: String, depth: Integer) extends Actor {

receptionist ! CrawlRequest(url, depth)

def receive = {

case CrawlResponse(root, links) =>

println(s"Root: $root")

println(s"Links: ${links.toList.sortWith(_.length < _.length).mkString("\n")}")

println("=========")

println(s"Current Time ${System.currentTimeMillis}")

}

}

Conclusion

The Actor Model has been around for quite a while (invented by Carl Hewitt et al in 1973) but in these past few years we have seen an increasing interest in Actors within the industry (Akka, Orleans, Erlang) due to their inherent ability to simplify concurrent problems and their ability to take advantage of distributed resources (a later post will follow later on). The full code listing can be found on Github :octocat:. Stay safe! Keep hacking!